This week, a planned protest by climate activists forced the closure of a major art museum in Boston.

Though the activist group in question, Extinction Rebellion, claimed they were not planning to damage the art, the staff of the museum did not want to take any chances.

Over the past year, about two dozen priceless paintings have been attacked by climate activists in museums throughout North America, Europe, and Australia, in some cases causing significant damage.

Just Stop Oil activists glued themselves to Vermeer’s iconic Girl With a Pearl Earring, Klimt’s Life and Death was splashed with oily liquid, and Van Gogh’s The Sower was slathered in pea soup.

The activists’ rhetorical calculus seems to be: “What’s a little soup on a masterpiece when planetary extinction is nigh? Better steal the spotlight and ‘raise awareness’.”

Such zealotry has been seen before in the millenarianism of many fundamentalist sects of the distant and not-too-distant past. (Guyana springs to mind.)

Indeed, this isn’t even the first time that the notion of an impending apocalypse has been used as a pretext for destroying art. I am reminded of the time I met the godfather of artistic apocalypticism himself.

Allow me to elaborate.

I was once invited to speak at a British Library event on the modern avant-garde called “A Slap in the Face of Public Taste: The Art of Manifestos.” I had every expectation that this would be one of those epicene, staid academic panel discussions where things get discussed but little gets memorably said. But for some reason, this event got billed, at the last minute and by word of mouth, as a “fiery debate.”

But once onstage, there under the spotlights before a half-filled auditorium, I found it hard to pound the table and raise my voice, to simulate, say, the air-raid typographies of Marinetti’s Zang Tumb Tuuum “sound poem.” Instead, I was my usual, affable, soft-spoken self.

What made me hold back?

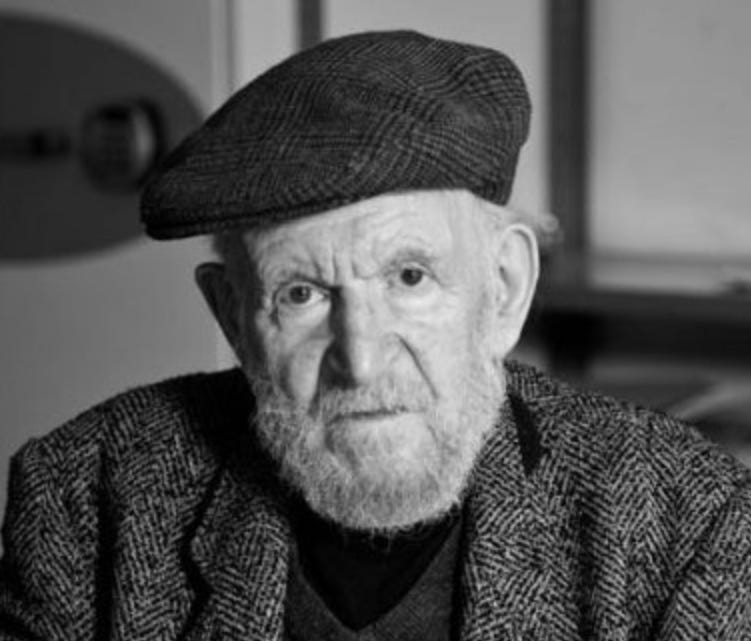

I looked across the stage to see my rival in this alleged “debate.” It was none other than a trembling, frail Gustav Metzger, a longtime fixture in the British art scene, just two weeks shy of his 82nd birthday and looking like he was about to fall over and dissolve to dust—much like his art was known to do. I couldn’t for the life of me bring myself to publicly rail against him, though I secretly wanted to.

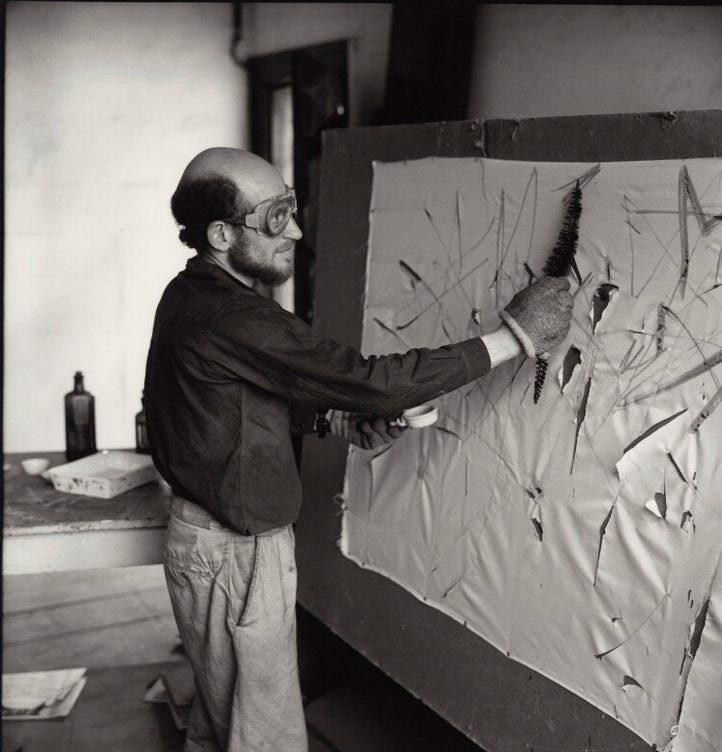

By the early 1960s, Metzger had become notorious in England for his “Auto-Destructive Art.” He would stand before a white rectangular canvas and brandish a giant paintbrush in the air with a flourish, like a Rembrandt from central casting. Yet suddenly his canvas would begin to disintegrate, revealing that his paint was actually hydrochloric acid, his “canvas” a rapidly dissolving sheet of nylon. This was Metzger’s big auto-destructive breakthrough—“Acid Action Painting.”

The theoretical foundation of Metzger’s practice is delineated in his 1961 manifesto. There, he explains how his work is intended as a commentary on mankind’s ability to destroy itself with nuclear weapons. Auto-destructive art simply reenacts—or, more accurately, pre-enacts—an impending nuclear holocaust and, as his manifesto puts it, the “drop drop dropping of HH bombs.”

Throughout the 1960s, Metzger toyed with variations on this auto-destructive motif, incorporating acid sprays, corrosives, ballistics, electric shocks—any means to render art objects null and void.

We might find a work of art that destroys itself to be momentarily amusing, which is strange considering the impending hellfire to which the artwork allegedly responds or refers. It is hard to wrap one’s head around the correspondence between the destruction of this particular work of art and the general devastation that a nuclear war would bring upon us. Though timely, such art tends to trivialize, consigning the apocalypse to a ham-handed novelty act. Yet Metzger was able to parlay this one neat trick into an artistic career and a large, if disintegrating, oeuvre.[1]

But a common complaint often levied against modern (and particularly postmodern) art is that it relies too heavily on theory; Metzger’s work is no exception. In fact, despite his passion for auto-destructive art, he typically carves out a loophole for his art’s accompanying texts.

While his canvases dissolve, the various manifestos that explain the necessity of this dissolving never vanish themselves as if written on flash paper or in disappearing ink. Rather, they are published in standard ways and survive to this day in climate-controlled archives. Thus, with the advent of “Auto-Destructive Art,” art gets literally replaced by an artistic theory that explains why there should be no art.

I knew all this going in. The British Library had invited me to speak that night because I had recently written an essay that reviewed the avant-garde arts manifestos of the previous century—an essay that also harbored sly pretensions of being an arts manifesto itself. It was called “How to Write an Avant-Garde Manifesto,” and I accentuated its pretentiousness by tacking it, 95 theses-like, to the door of the Institute of Contemporary Arts on The Mall, a longtime haunt of Metzger, Yoko Ono, and other pretentious avant-gardes. So, I was in good company.

But since I had written the essay, I knew Metzger was in good company, too. He wasn’t the first avant-garde artist to subject art to destruction, derision, or debasement. The project of “conceptual art” to take the art object down a few pegs got going in earnest in 1917, when Marcel Duchamp signed a porcelain urinal “R. Mutt” and called it sculpture. Voila: Anti-Art.

I’m not here to rail against Duchamp’s inaugural act as some kind of transgression or heresy, nor to praise it as a bold statement about the ontological status of art. To me, it seems playfully provocative and innocent enough. And I don’t necessarily condemn all conceptual art, though most of it seems pretty meh. I could catalogue its crimes: the shit tins of Piero Manzoni; the spiced-out writhings of fraternity little sisters, courtesy of Tino Sehgal. What I mainly want to focus on is a specific tendency: the degree to which conceptual artists like Metzger—all who followed in Duchamp’s wake to make their own “profound statements”—often end up reifying the “problems” that their art is allegedly intended to critique, oppose, or “raise awareness about.”

Take the Dadaist movement. Born out of World War I, the movement eschewed the typical avant-garde plan of propounding pros and cons, blessings and blasts. The Dadaists felt that drawing sharp lines between accepted and rejected dogmas was too much a process of rational thought; it was too involved in the logic of territoriality and dialectical debate—the very things that, they imagined, caused the war. Thus, their manifesto mocked the idea of having clear goals, of wanting “ABC” and fulminating against “1,2,3.” But isn’t the embrace of goallessness itself a goal—a goal of mocking those with a more goal-oriented agenda? By rejecting the idea of having goals, the Dadaists became that which they claimed to reject, dialectically pitted against dialecticism per se.

Faced with the absurdity of such paradoxes and contradictions and the absurdity of industrial-scale warfare, the Dadaists, and then the Surrealists, started embracing and promoting heightened levels of absurdity for their own sake or for no reason at all. Here again, conceptual art’s critique blends seamlessly into symptom.

Back to Metzger and his Cassandra-like canvasses. They seem to me now more than just a warning of impending nuclear war. They are a prelude to, but also a manifestation of devastation, perpetuating the downer meme that nothing is worth doing since it will most likely be instantly undone.

It is impossible not to notice that much of what emerged after World War II, in the era of nuclear weapons, carries with it a similar theme. Buildings, art, poetry—all seem either a mindless lump of forms or else conspicuously whimsical, as if expecting to be rendered obsolete or nonexistent at any moment.

In the war’s aftermath and since the advent of the bomb, European society seems irreconcilably bifurcated: one part yearns for and clings to a pre-nuclear past characterized by made-to-last, aesthetically pleasing creations, while the other grapples with a post-nuclear reality defined by disposability, interchangeability, infinity immigrants, microaggression policing, sweatshop slop, and fast food prolefeed.

Like Metzger’s work, much of the flimsier, conceptual art that now surrounds us warns of an annihilation. But it’s an annihilation that remains unrealized, except insofar as the works themselves have annihilated, or have attempted to annihilate, our collective spirit.

The bomb, in a sense, has already dropped on us.

The bomb? That was yesterday’s apocalypse. That’s boomer-tierdoomposting.

Extinction Rebellion and Just Stop Oil don’t even bring the issue up, and yet they still insist that we are all quite doomed.

Is it any surprise they so blithely destroy art?

[1] Though Metzger later would explore “Auto-Creative Art,” it is his earlier destructive tendencies for which he is remembered—in addition to inspiring Pete Townshend to smash his guitar.